Are you sure you want to delete your account?

(This will permanently delete all of your data - purchases, game scores, ratings, etc)

Change your username

Your current username is: guest

Change your account email address

Your current account email is:

Redeem your Fampay code here!

Use your Fampay code to get access to the Play Magnus Plus Membership!

Why Do We Miss Good Moves? – Part II

Have you checked the first part of the series about why we miss good moves in chess? I do hope that it has helped you somewhat reduce the number of blunders in your games. Still, to err is only human, so you will never be able to eliminate all the mistakes from your play. Anyway, let me share with you a few more tips on what you could do to take your game to the next level.

Stylistic preferences (deficiencies)

Some years ago, I asked GM Arkadij Naiditsch whether it would be better for me to develop my style by studying the games of attacking players or to eliminate my shortcomings by reviewing strategic masterpieces. Being a rather categorical person, he replied: “You are too weak to have a style. Study everything!” That being said, you should take his comment with a grain of salt since, at that time, he seemed to consider all players rated below 2700 to be more or less patzers. Anyway, I would like to point out that our chess weaknesses do lead to poor decisions over the board.

In a perfect world, we should all be striving to become universal players. However, perfection knows no limits. How do you start? A serious topic that has been hotly debated for years: should you rather focus on developing your strengths or prioritize getting rid of weaknesses? My opinion is that usually, it’s easier and more sensible to improve where you are naturally gifted. However, you will have great returns initially by focusing on what you do poorly. It’s just important not to get overzealous. Let’s say you have no clue about endgames. Spending about 50 hours to familiarize yourself with the most popular 100 theoretical endgames would boost your strength considerably. However, if you are not a fan of the endgame and have no natural feel for it, you may end up spending hundreds of hours going over endgames played by masters without really improving much in that department. And, in contrast, if you are a natural-born attacker who spends the same amount of time on tactics and typical middlegame attacking plans, your rating will grow much faster.

Speaking about poor decisions caused by stylistic preferences, I have been loyal to the perception of myself as a tactical and witty player for quite a long time, so I used to run like the plague from exchanging queens. I wasn’t confident in my ability to convert a better endgame; didn’t evaluate well enough positions without queens on the board; felt like I would get more chances to win material or checkmate my opponents if the queens stayed. This is a typical chess deficiency, especially at the club level. I have to admit that I still haven’t solved the problem entirely, but having gone through many endings, endgame studies, and typical positions has improved my understanding and knowledge of the final stage of the game. As a result, nowadays, I am more willing to trade queens if it offers me certain benefits. Amusingly, this has even led to a few situations where I have talked myself into trading queens in positions where it was more lucrative to keep them on the board!

Non-chess reasons

Feeling sick, being hungry or drowsy, losing concentration, and other similar reasons dramatically influence our tournament performances. Sometimes your mind starts wandering elsewhere and thinking about the next round game, your family relationships, how to spend the evening – anything but chess! Even for chess pros, it is quite tough to maintain a high concentration level throughout the game, especially when not being in the best physical and psychological shapes. Some of the World Chess Championship contenders bring up such reasons for losing the matches as strained family relationships, lawsuits, conflicts within the team, health issues, hypnotizers working for the other guy, etc. Of course, you can waive some of the arguments off as not serious enough or as made-up excuses, but the Grandmasters would probably not agree!

As you can see, even at the very top level, the outcome of the game is often determined not purely by who is the better player here and now but by many other factors. The more of them are in your favor compared to your opponent, the higher the chance to succeed. Of course, this sounds a bit like the “it’s better to be healthy and rich than sick and poor” tip of advice, but your performance could indeed improve if you honestly assess yourself in non-chess departments and make notes on what can be done better.

Losing objectivity and patience

If the twist of events in the game is unfavorable for us, sometimes it is tough to admit it and to adapt to the changes. Many encounters have been lost due to stubbornness and unwillingness to acknowledge the obvious. For example, a person who had a considerable advantage might blunder and keep playing on as if he is still way ahead. Trying to break the laws of chess leads to painful defeats.

Another common chess sin is losing patience. There are an amazing number of players who can’t handle the tension of playing long games, especially if the position is not to their liking. For example, most amateur players, especially young and impatient ones, have no clue what to do in “boring” endgames or positional struggles. They always try to get something going as soon as possible, even if it comes at the cost of damaging their positions. Older people have another problem: they typically get tired and start feeling like they should finish the game as soon as possible regardless of the result since otherwise they will lose focus at some point and self-destruct. Chess is a cruel sport for them: quite often, elderly players can be seen begging for draws or blundering terribly when ahead on the board.

Finally, there is that typical case of getting punished for being impatient to convert a winning advantage asap. A good illustration of this scenario is Viktor Korchnoi’s performance in Linares Anibal Open’1998. Viktor (2625) managed to trap the opponent’s queen early on in the game and to win material. His lower-rated opponent Julian Estrada (2395) didn’t give him any credit and continued playing as usual. The two times runner-up of the World Chess Championship became infuriated and started blitzing out the moves only to blunder a queen in return and lose! However, when a similar situation occurred in one of the following rounds, the veteran showed that he has learned the lesson and managed to convert the game in style.

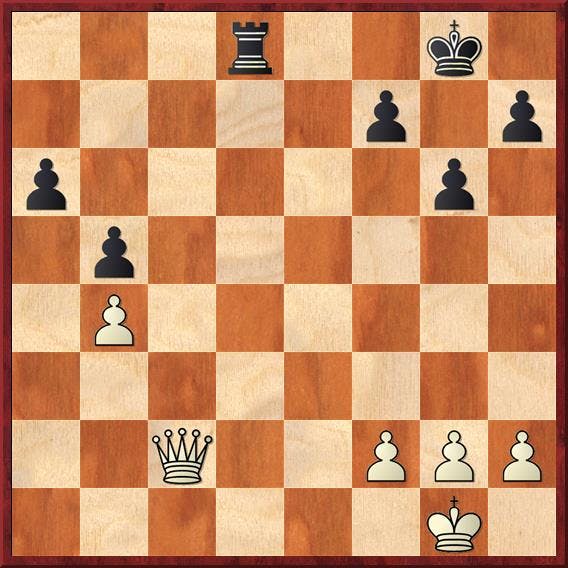

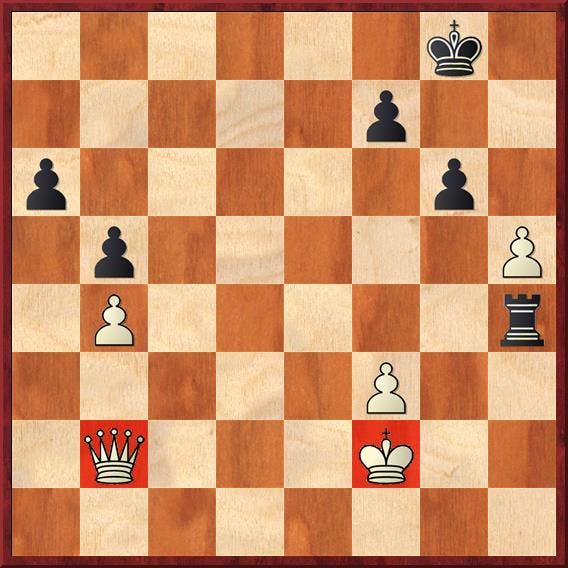

Here it is Korchnoi’s turn. He is White and has a queen for a rook and a pawn, which should be an easy win. Typically, you indeed don’t play on in such positions against a former World Chess Championship challenger.

A few moves later, we can see that White made life more difficult for himself. But what followed next is “inexplicable”. Korchnoi hastily played 41.hxg6 and resigned after the obvious 41…Rh2+, picking up the queen with a skewer. As usual for such cases, his opponent got to hear what Viktor the Terrible thought about his manners and chess skills!

Summarizing, if you do a careful performance review based on the six areas of improvement mentioned in the first and second parts of the series about missing good moves and follow at least some of the recommendations, you should definitely improve as a chess player.

However important general chess tips are, they are no replacement for studying eye-opening chess lessons and doing tricky training exercises. Check out Magnus Trainer for a course recommended by the reigning World Chess Champion himself!